An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 39 (of 95 parts) - Sutton Crime & Court Cases - Part 2

b) Madman in Sutton Monastery | c) A Policeman's Lot Was Not a Happy One!

d) The Shooting of Michael Noonan | e) The Legal and Illegal Beating of Boys

f) Seduction of a Sutton Builder’s Daughter | g) Brutal Murder of Walter Davies

h) Red Tape in Old Sutton | i) A Case of Poetic Justice within Sutton Manor

j) Strange Case of Alderman Boscow | k) Sutton Judge Sir Bernard Caulfield

Also See: Sutton Crime Part 1 | Sutton Crime Part 3 (in brief) | Sutton Tragedy Part 1

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX Contact Me Research Sources

A Madman in Sutton Monastery

A Policeman's Lot Was Not a Happy One!

The Shooting of Michael Noonan

The Legal and Illegal Beating of Boys

Seduction of a Sutton Builder’s Daughter

Brutal Murder of Walter Davies

Red Tape in Old Sutton

A Case of Poetic Justice within Sutton Manor

The Strange Case of Alderman Boscow

Sutton Judge Sir Bernard Caulfield

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

Old Sutton in St Helens

Madman in Sutton Monastery

Policeman's Lot Not Happy

Shooting of Michael Noonan

Legal & Illegal Beating of Boys

Seduction of Builder’s Daughter

Brutal Murder of Walter Davies

Red Tape in Old Sutton

Poetic Justice in Sutton Manor

Strange Case of Ald. Boscow

Sutton Judge Bernard Caulfield

The Case of Breach of Promise and Seduction of a 17-Year-Old Sutton Girl

A not uncommon court case during the Victorian era was breach of promise of marriage. It usually involved women suing men for damages, although sometimes men were plaintiffs. These days many young people think nothing of ‘dumping’ their boy or girlfriends verbally or by text message. However, in the past, when respectability and reputation were all-important, there was shame and embarrassment in being rejected or jilted, which could be ameliorated by money.The damages that courts awarded varied, but they could be quite substantial and well worth the airing of dirty linen in public. In an article on December 16th 1865, the Penny Illustrated Paper complained how in two very similar breach of promise cases, a Mr. Da Costa had been forced to pay £2500 and a Mr. Kendall £70 in damages. They couldn’t understand how different juries considered Da Costa to be 35 times 'more depraved' than Kendall. However, £70 in the 1860s was worth about £3000 in today’s money, so it wasn’t to be sneezed at.

Magistrates only had the power to award damages of up to £15, and with St.Helens not being a County Borough until 1889, plaintiffs had until then to go elsewhere for justice. So when Critchley v. Greenough, took place on May 14th, 1874, it was held in Preston’s Sheriff Court. The case was complicated by 17-years-old Margaret Anjou Critchley being made pregnant by Joseph Greenough, a fitter at Sutton Glass Works. So Margaret’s father, James, brought an action for seduction and breach of promise against him.

James Critchley was the landlord of the Mechanics Arms in Sutton, which he took over in 1870. This was then located at 38 Peckers Hill, soon to be renamed Ellamsbridge Road. Greenough drank at the beerhouse and became quite enamoured with Margaret, who was then probably only 15. She worked as a bar maid and according to court testimony, Greenough began “paying his addresses” to the girl. Soon the couple became engaged with the approval of the parents. In May 1873 Margaret discovered that she was pregnant, or 'enciente', as it was more delicately put in court. After Margaret’s father, James had what was described as 'a conversation' with Greenough, the young man went to a Widnes church where the 'askings' or the banns of marriage were put up.

However, Greenough got cold feet and just before the wedding and bolted to Belfast, leaving his intended in the lurch. Margaret had been forced to leave the family home when her condition became known, but a friend interceded with the parents and she was allowed back to the pub. Some weeks later Greenough returned to Sutton, apologised for his actions and repeatedly assured the family that he would do the right thing and marry Margaret.

How the Penny Illustrated Paper depicted scenes from Victorian breach of promise cases

Scenes from breach of promise cases depicted by the Penny Illustrated Paper

How the Penny Illustrated Paper depicted breach of promise cases

Not all marriage proposals ended in marriage!

Still Greenough promised to marry her. However, by January 1874 there were rumours that he was carrying on a "sly courtship" with a woman called Elizabeth Thorpe, who was said to be worth £1000. When the Critchleys challenged Greenough, he vehemently denied any such affair, but then proceeded to marry Elizabeth! This was the final straw for James Critchley and his wife Jane, and so they began legal action on behalf of their daughter.

Their solicitor claimed in court that Margaret had no longer any opportunity of marrying respectably and she had been ruined for life. A substantial sum was demanded in compensation. However, Greenough only earned 34 shillings per week, with overtime taking his earnings to just over £2. It was stated that the glassworks fitter did have a share in some property in St.Helens but the value was disputed. A child maintenance order was not an option for the jury, who decided that the Critchleys deserved a £150 'solatium', a one-off payment somewhat on the low side of the compensatory scale.

Just what happened to Margaret isn't known. Unmarried mothers were treated harshly by parents and society with many put in mental hospitals. Although initially the Critchleys had ordered their daughter out of their house, they seemed to have become more sympathetic to her plight. There's every chance that James Critchley took over the license of another pub in another town and perhaps he and his wife Jane brought up Margaret's children as their own. Hopefully, Margaret managed to make something of her life. It's one of the frustrations in researching stories like this, there are always loose ends that you know are unlikely to be resolved.

UPDATE BY NICOLA BURKE: Margaret was my husband’s great-great Grandmother. She married George Code in 1878 and her child Frederick was raised as their own and they went on to have 6 more children. George was from Ireland and had been a sailor on the ship Thalia, having travelled around the world as far as Hong Kong. He settled with Margaret in Horwich near Bolton and got work at the Locomotives Factory. Having read this story I assume George met Margaret at her father’s pub but who knows. From records it appears Frederick died in 1881 aged only 8. I am not aware of another child by Joseph Greenhough. Margaret passed away in Horwich in 1931, with George having passed away in 1917. It is a very interesting story and George Code must have been a kind man knowing Margaret’s predicament.

A Madman in Sutton Monastery

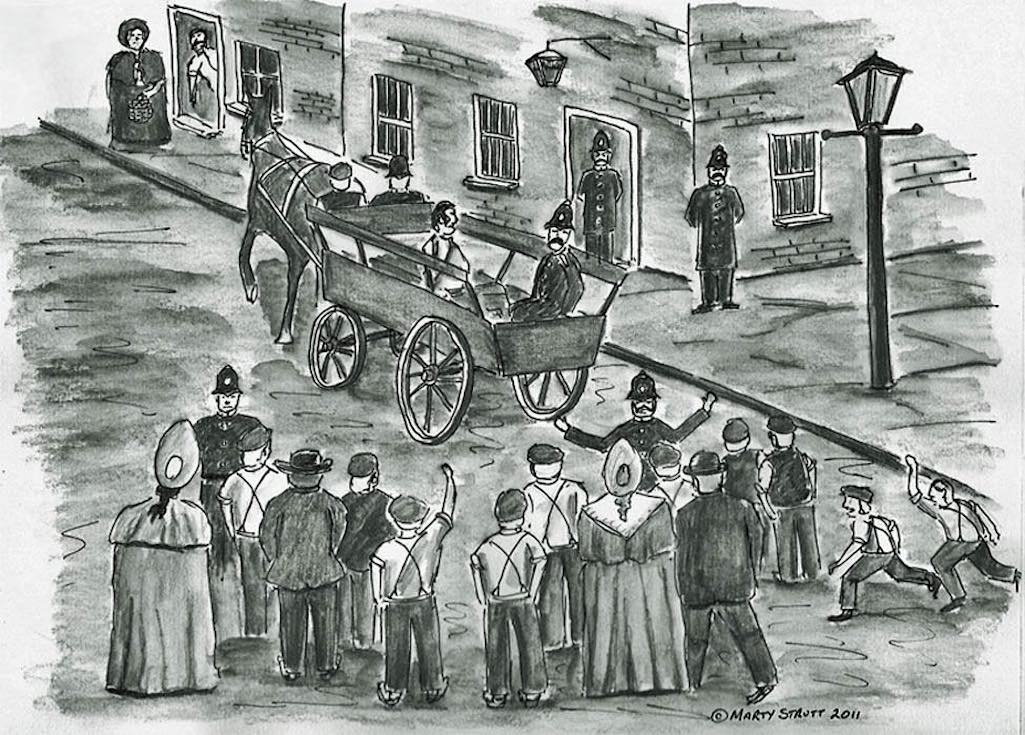

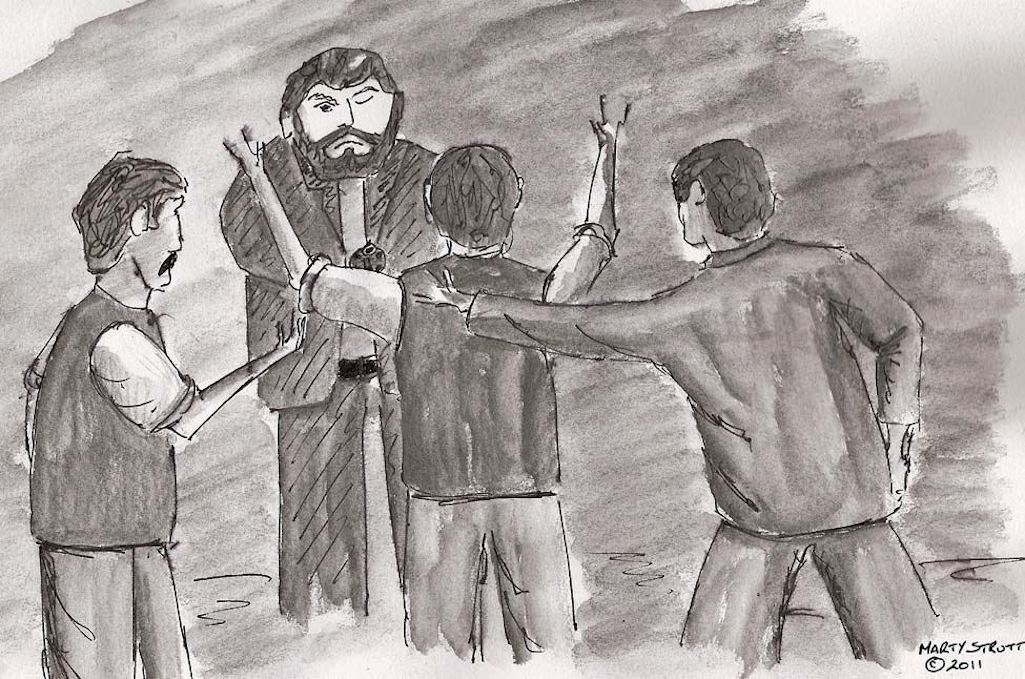

St. Anne’s monastery from time to time attracted oddballs and thieves, thinking they could take advantage of the fathers. On December 2nd 1881, a vagrant called William Towers appeared in St. Helens Police Court charged with theft. He’d been to the monastery as part of a 'begging tour', which had also taken him to Charles Walsh's draper's shop in Peckers Hill and Mrs. Platt's shop in Worsley Brow. At the monastery Towers stole a book 'The Casket of Literature' and from the two shops had helped himself to a jacket, shirt, braces and pinafores. Towers was arrested trying to pawn his ill-gotten gains and received sixty-three days in prison. Then on November 3rd 1884, Daniel Walsh was sent to prison for six months with hard labour. He'd been employed at the monastery and had taken eleven books worth £1 17s 6d.One of the strangest oddballs – that the Liverpool Mercury unkindly dubbed a 'maniac', 'madman' and 'lunatic' – was John Carroll of Ditch Hillock in Sutton. On Saturday March 19th 1870, Carroll visited St.Anne’s Retreat and took a large quantity of the monastery’s books and effects. He had a wild notion that the monks owed him £2000 and as they refused to pay him, he decided to take it in kind.

The Ditch Hillock area is now known as Waterdale Crescent and is just around the corner from the former monastery. The police searched John Carroll’s home on the Saturday evening, where they found much monastery property. Believing that he had the right to possess these goods, Carroll become violent when the police seized them. So the boys in blue tied his legs, handcuffed him and placed him inside a cart.

A Marty Strutt illustration of John Carroll arriving at the police station - 'Move along now...nothing to see here!'

A Marty Strutt illustration depicting John Carroll arriving at the police station

John Carroll arrives at the police station

The Liverpool Mercury's headline to their article was ‘A Madman in a Monastery’. Just like today, the newspapers in Victorian times did, at times, like to sensationalise and alliterate.

A Sutton Policeman’s Lot Was Not a Happy One!

The priests from St.Anne's were renowned for getting on their bikes and pedalling to where there was trouble. The pugilists and rowdies would show respect to the men of the cloth and stop their fights. However, the police could not always expect such courtesy. On September 9th 1844, five Farnworth weavers were charged with assaulting parochial constable Thomas Smith in the Griffin Inn in Bold Heath. The Liverpool Mercury of September 27th said they gave him a 'pair of handsome black eyes' after he'd intervened in a fight. The magistrates dismissed the charges and severely reprimanded the constable for initially encouraging the fight.

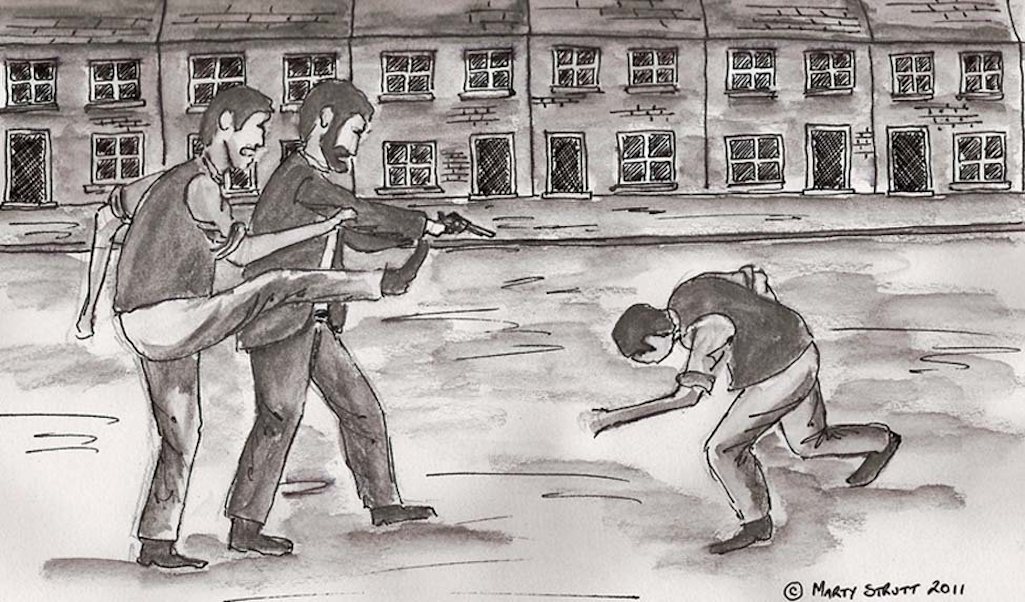

On August 28th 1855, Sutton shoemaker Joseph Tickle was fined twenty shillings for assaulting constable Thomas McFarlane. He'd been trying to stop a drunken fight in Peasley Cross between beerseller William Anders and Sutton wheelwright James Webster. Tickle disliked the interference and so struck McFarlane. On February 12th 1881, Constable Banks came across a group of five men in Sutton who were causing a disturbance. He told them to go home but instead they attacked him. The thugs beat and kicked him, breaking the policeman’s elbow. One of them, Edward Littler, was handcuffed by PC Banks, but he escaped and went on the run. Over two years later, Littler's brother turned him in and on October 5th 1883, the fugitive appeared before St.Helens Police Court to face justice. Just how PC Banks felt when Littler was fined just five shillings, isn't recorded!

On June 27th of that same year, John Fairclough appeared in court charged with being drunk and disorderly and assaulting P.C. Carter. The incident had happened in Marshalls Cross Road, late on the previous Saturday night. Two women and a man had approached the constable at 11:30pm to report that Fairclough had been following them from St.Helens and kept grabbing hold of the women. The defendant then arrived making what was described as a 'great noise', cursing and swearing. The constable took him to his sister's house but Fairclough wouldn't remain there, so was taken into custody and a violent struggle began. P.C. Carter was reported to have been kicked in a 'tender part', and had endured great pain since. In a separate incident earlier that same day, John Fairclough had assaulted P.C. Wellwood and had been before the court on seven previous occasions. For both offences he was fined 40 shillings each.

On June 1st 1891, Albert Jones of 15, Worsley Brow appeared in court charged with assaulting Police Constable Cooper. He’d thrown him to the ground then gave him a good kicking about the legs and body. He was fined just 2s. 6d. On October 5th 1891, Thomas Ashcroft of Ell Bess Lane (now Sherdley Road) appeared in court charged with striking PC Evans. The constable had taken Ashcroft’s brother into custody, so he punched him in the mouth. The magistrates fined him ten shillings.

A few shillings was a lot of money to poor Suttoners in those days, with manual labourers at collieries and factories only earning about 18 to 20 shillings per week. However the fines were still quite mild for the violent offences committed. On December 27th 1897, Henry Whaling from Sutton appeared in court charged with being drunk and assaulting Police Constable Peters. After the officer had warned him about his conduct, Whaling tripped him up and then gave him a kicking. He was fined five shillings for the drunkenness and ten shillings for the assault.

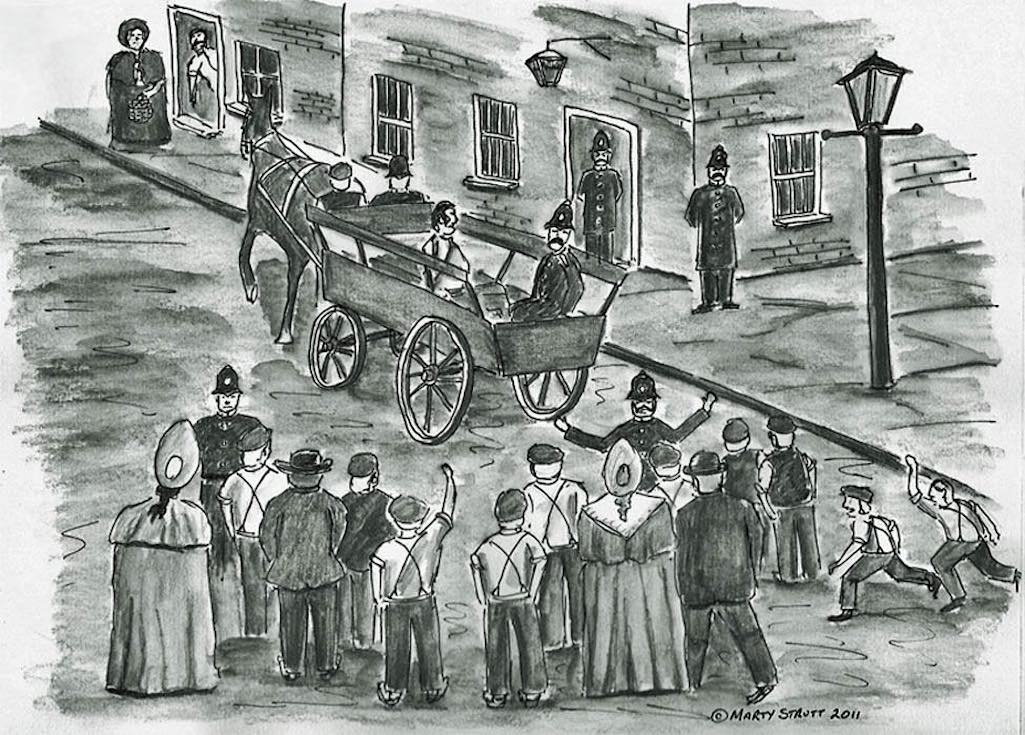

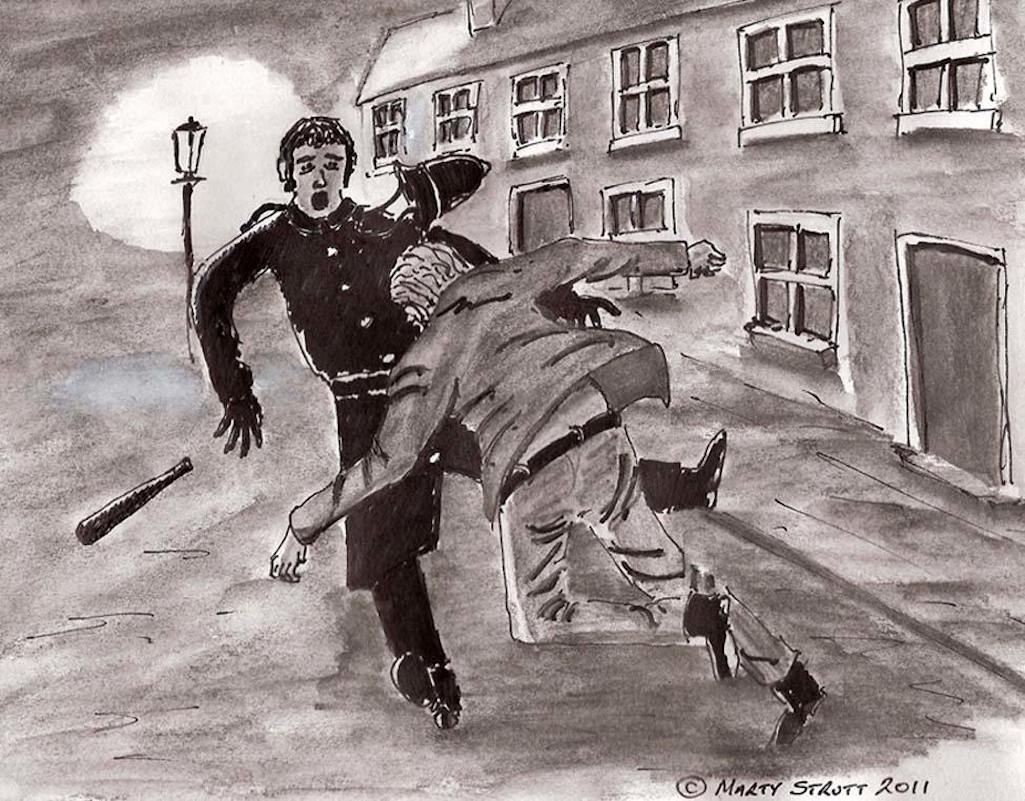

A Marty Strutt illustration of the one-hour struggle between Peter Duckworth of New Street and PC Staveley

An illustration of the struggle between Peter Duckworth and PC Staveley

Illustration of the struggle between Peter Duckworth and PC Staveley

The fugitive was subsequently arrested by Sergeants Jackson and Roby, but not without a fight. In another very violent assault, both officers were attacked by Duckworth and Sgt. Roby was kicked about his legs until unable to stand. In court Peter Duckworth blamed his behaviour on drink and pleaded with the bench for another chance. Due to the seriousness of his assaults, and the fact he'd been imprisoned for 6 years whilst in the army, Duckworth was instead sent to prison.

By the early years of the twentieth century there was less tolerance of violence and assaulting a policemen was taken more seriously, although it was still highly prevalent. On July 25th 1914 Chief Constable Ellerington complained to the St.Helens magistrates that people were "playing pitch and toss" with his officers and in some districts men "set upon them like bulldogs". Two days later when two men were sent to prison for 12 months and 9 months for a vicious assault on a policeman, it was revealed by the Chief Constable that there'd already been 40 assaults on the St.Helens police that year.

Then on August 14th 1915, magistrate J. B. Leach (of the estate agency family) sentenced a man at St.Helens Police Court to 28 days hard labour for attacking a bobby. He said: "We do not pay for policemen to be knocked about in the street". As Gilbert & Sullivan said in Pirates of Penzance, a bobby's lot was not always a happy one. But it began to improve with deterrent sentences for their attackers, motorised transport and then radio communications.

A Sutton bobby in Junction Lane

Shooting of Michael Noonan

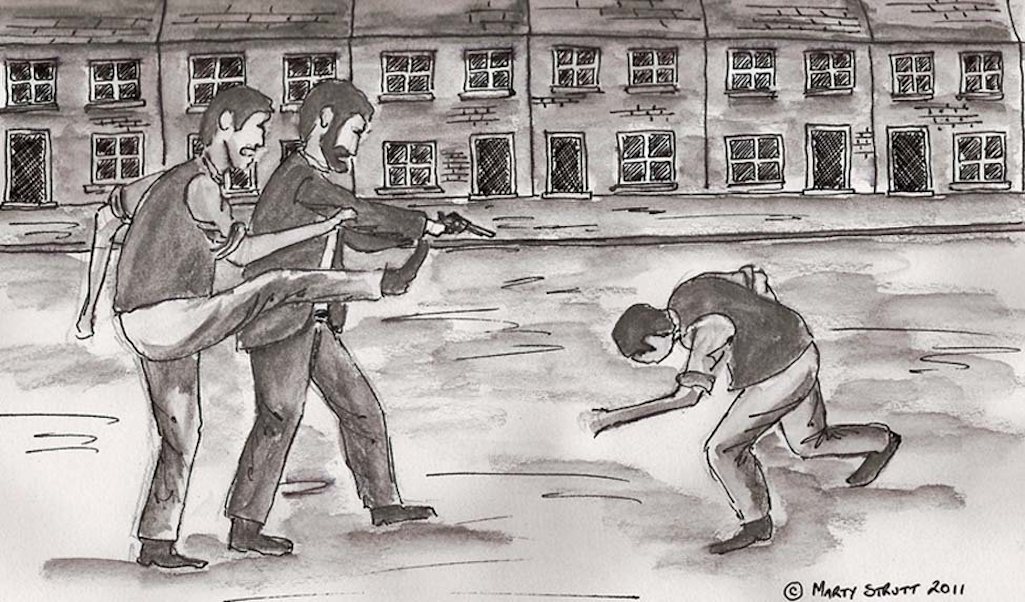

Over the last 100 years there have been many improvements in the judicial process with the advent of new technologies, forensics and detection methods. Policing methods and the conduct of court cases have changed much and they’d had to reflect social changes within society too. However people are in many ways just the same and often in court it can still be one person’s version of events against another’s. Like two football managers on Match of the Day giving contrasting post-match opinions on incidents within a game, people’s perceptions of the same reality can be drastically different. Juries have to try and make sense of differing witness accounts and even prosecution and defence ‘experts’ can offer opposing views. Ultimately it’s down to jurors to state their own opinions as to innocence or guilt, which was an even tougher task a century ago. Especially when a guilty verdict was likely to be a death sentence for the prisoner.The jury in the 1902 murder trial of James Shaw were faced with two polarised versions of how he came to shoot Michael Noonan. The prosecution and two eye-witnesses – Thomas Noonan and Alfred Ashton - stated that it was a pre-meditated act. However the defendant claimed that he'd been attacked by the deceased along with the eye-witnesses and his gun had accidentally been discharged.

This court case was extensively reported in the local press and reveals a number of interesting issues. This article will explore these in four sections describing: 1) the background to the case and what was undisputed; 2) the prosecution's version of events; 3) defendant’s version; 4) trial issues and verdict.

Shaw often carried a gun with him when out drinking. It could sometimes be seen inside his pocket by the Boilermaker’s landlord Alfred Hardy and fellow drinkers. However he carried it in two sections and the gun’s barrel and stock had to be assembled for use. Although Shaw had a licence for his weapon, it had expired five days before it took the life of Michael Noonan. He had a history of poaching having first been convicted on August 11th 1893 after being spotted by the police leaving Sherdley Park at 4am. Shaw was carrying a loaded gun and his accomplice had a newly-shot hare inside a coat pocket. He was fined 20 shillings for the poaching but was back in court three weeks later when his landlord tried to have him evicted for non-payment of rent.

On the night of August 5th 1902, the Noonan brothers and Alf Ashton were drinking in the Boilermaker’s. James Shaw was also present with his pals James Dixon, Thomas Tarpey and Fred Gaiter and Shaw also had a black dog with him. A game of 'tippit' was played in the pub and Michael Noonan and Dixon were known to have participated. This popular coin game may have caused the disagreement, although it was never made clear. The Noonans and Ashton departed the Boilermaker's just before 10pm, shortly after Shaw’s group had left the pub. Miners were renowned for setting disputes with their fists and at some point on their journey home, the two groups met and fought one other in the street. After the Noonans had won the fight, James Shaw produced his gun and Michael Noonan was shot in the abdomen. He was taken to his home at the back of Berry’s Lane but despite the efforts of Dr. Casey, died at quarter to midnight.

The St.Helens Reporter of August 8th said that before Michael passed away, his brother Thomas had comforted him saying: "Tha will be a'reet in the morning, after tha's had a sleep". But the deceased bowed his head and said "No fear, Tom he has blown my inside out." Shaw meanwhile disappeared and the police undertook an extensive search to find him. At 8:30pm on Wednesday night - less than 24 hours after his death – Noonan’s inquest was held in St.Helens Town Hall. The jury of 18 men - led by foreman Thomas Yearsley and County Coroner Samuel Brighouse - inspected Noonan’s body and then listened to the police report and witness testimonies. The inquest was then adjourned.

Later that night the fugitive Shaw was captured by PC Richard Marsh outside his own home. After the shooting he’d spent the night out on the moss and then travelled to his mother-in-law’s house in Knutsford. Upon returning to Collins Green station, Shaw was spotted by the acting Station Master Lyons. He telephoned St.Helens Junction station to get a message to the police and PC Marsh arrested Shaw as he entered his back yard. The constable allowed him to have supper inside his house and say goodbye to his wife and eight children, before taking him in handcuffs to St.Helens Town Hall. It was reported that Shaw had returned to give himself up and clear his name.

Michael Noonan's funeral took place on Saturday 9th August at St.Anne’s RC Church. A crowd of 600 people assembled at the end of Berry's Lane to watch the procession leave Noonan's home. The cortege passed the Boilermaker's Arms which had closed its doors as a mark of respect. The last rites were conducted in the graveyard by Father Damien as Noonan was laid to rest.

These are the background facts as was known and undisputed. However just what had happened when the shot came to be fired was a matter of considerable contention.

Noonan claimed that on the night in question after leaving the Boilermaker’s, he and his brother Michael had had a brawl in the street with Dixon, Tarpey and Gaiter. Afterwards, accompanied by Alf Ashton, they spent some minutes searching for Michael’s cap which had become lost in the fight. The threesome then resumed their journey home but soon came across James Shaw, walking from the direction of his own house. Thomas claimed that Michael had said "Here’s James Shaw" to which Thomas replied "Come on home and never mind Shaw". His brother answered that "Me and Jim Shaw’s had no bother".

While they were talking, Shaw removed his gun’s stock and barrel from two of his inside pockets and assembled the weapon. Thomas Noonan then told the court that the defendant had walked up to his group and said "Here's Shaw" and fired at Michael from just six inches away. As his younger brother fell to the ground, Thomas began to tend to him but Shaw then pointed the gun at him. So Thomas leapt up and knocked him down. As Shaw rose, he made a threat to blow Thomas's brains out and so he knocked him down once again. The gun was spilled and Ashton and Shaw struggled for it, the former taking possession. As Shaw left the scene, he claimed he was going for another gun, still threatening to blow their brains own.

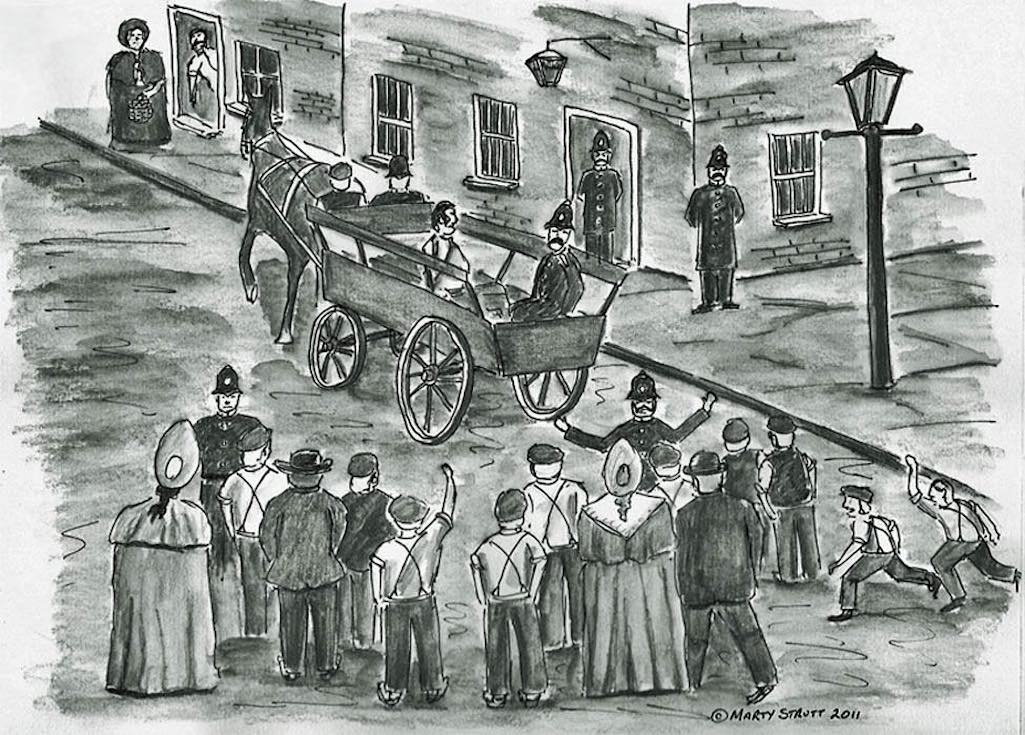

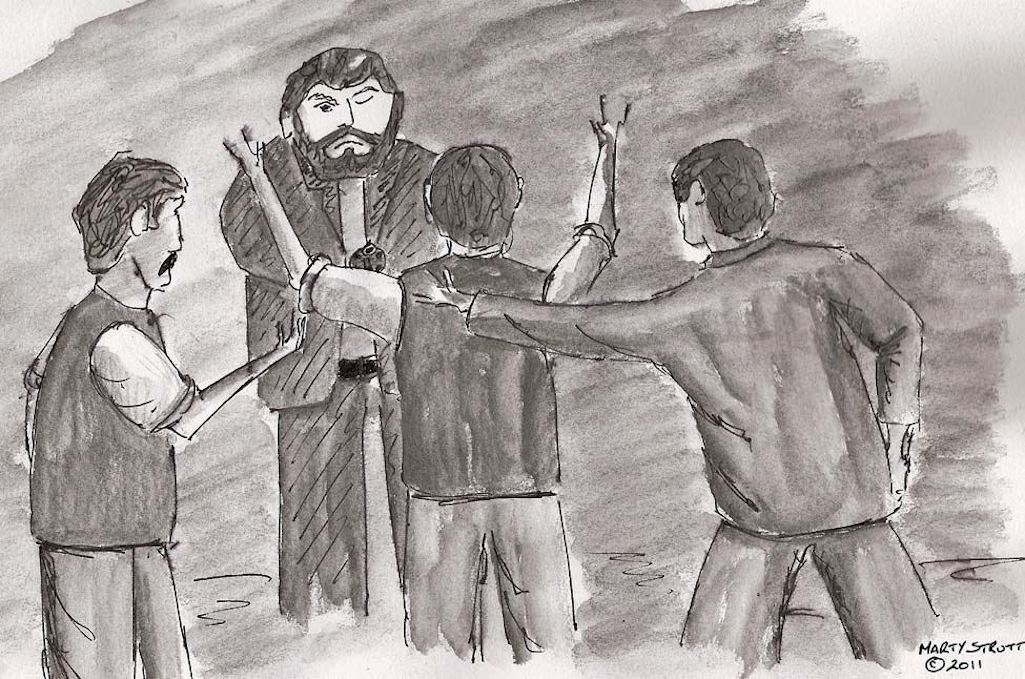

A Marty Strutt illustration of the prosecution version of how James Shaw came to shoot Michael Noonan

An illustration of the prosecution version of how Shaw shot Noonan

Illustration of the prosecution version of the shooting of Michael Noonan

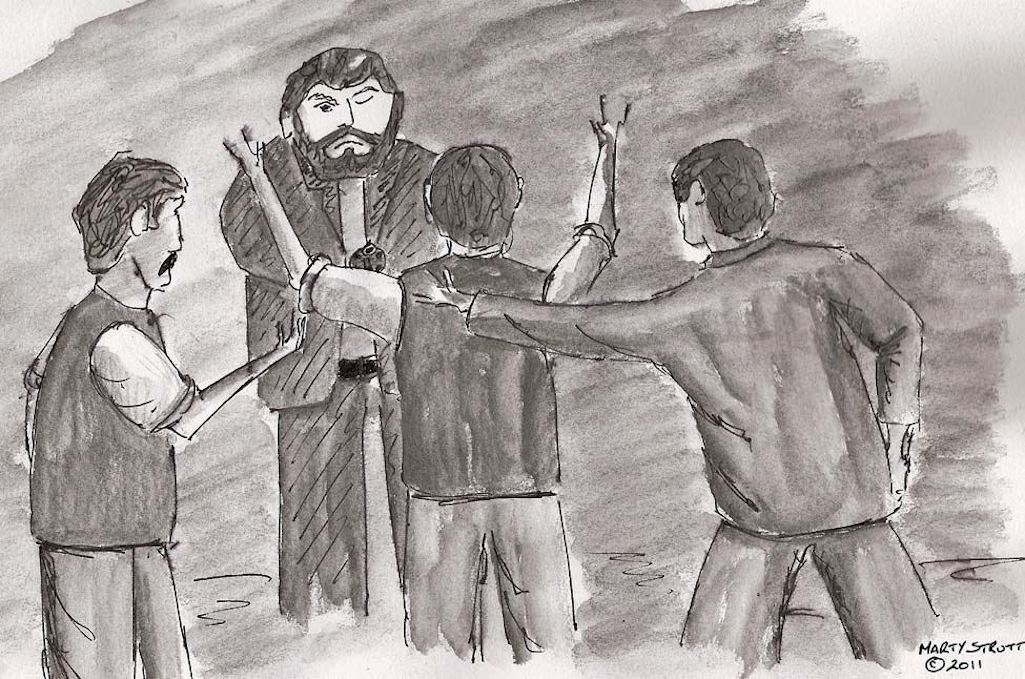

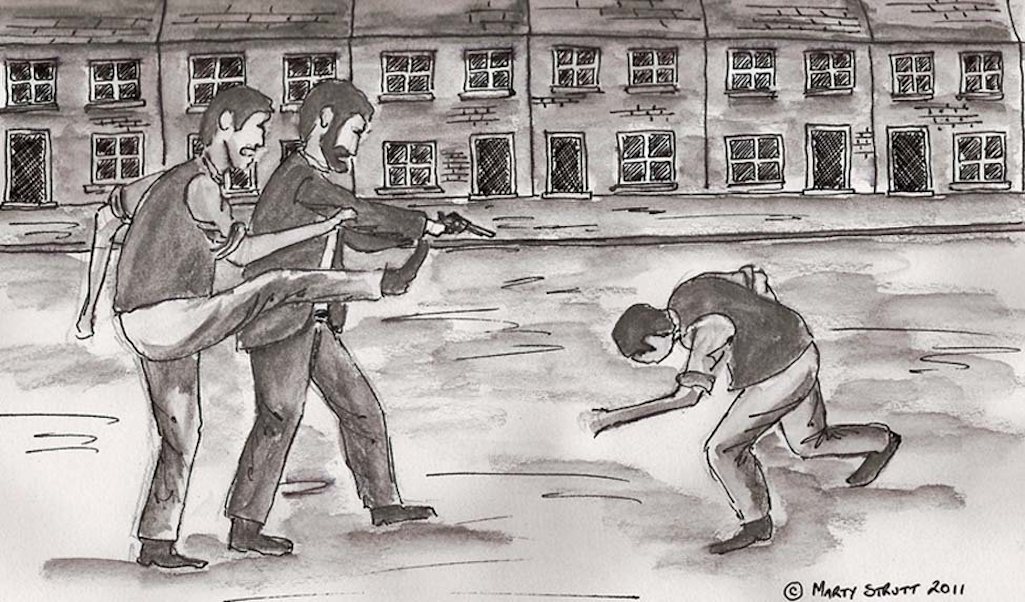

Shaw claimed that one of the men said "We’ll have thee and the gun and all" and the threesome then rushed him. Thomas Noonan hit Shaw twice on his forehead and then attempted to get the weapon off him by kicking his gun hand. In doing so the gun was fired and Michael Noonan - who had grabbed hold of the muzzle – received the fatal shot. At the moment it was discharged, Shaw was standing upright and his gun barrel was pointing down. The importance of this evidence becomes clear shortly.

Marty illustrates the defence version in which Thomas Noonan kicks Shaw's hand causing him to shoot Michael Noonan

The defence version in which Thomas Noonan kicks James Shaw's hand

Defence version Illustration in which Thomas Noonan kicks Shaw's hand

Secondly - and more importantly - the direction of travel of the bullet into Michael Noonan’s body was inconsistent with the eye-witness accounts. Doctors Unsworth and Casey gave evidence at the trial that the bullet had travelled in a downward direction as Shaw had testified. Thomas Noonan and Ashton had claimed that Michael was shot straight on, so the wound was into - and at right angles - to his body. These days ballistics experts would provide such expert testimony but family doctors a century ago were multi-skilled. They didn’t just hold surgeries and make home visits but they attended their patients in St.Helens Hospital and carried out many operations and autopsies.

Providing court testimony was also one of the doctors’ duties and Dr. Unsworth said Noonan would have had to be in a stooping position to receive such a wound. If the deceased was stood erect – as the eye witnesses had claimed – then the gun would have had to be almost vertical itself. The wound was about six inches deep and Dr. Unsworth had undertaken experiments that revealed that the muzzle of the gun must have been about one foot from the deceased when it was fired. There was a slight problem with James Shaw’s evidence as he insisted that he had the gun in the Boilermaker’s, but no witnesses could support this. This was important as if Shaw had had to go home for the weapon, as the eye-witnesses had claimed, then the premeditation of the killing was reinforced. However Shaw told his trial that people only ever saw his gun in the pub when he was drunk. He successfully demonstrated to the jury how he was able to keep it on his person out of sight.

In summing up to the jury, Judge Jelf remarked how the two stories were "diametrically opposite in every particular". If the two witnesses for the prosecution had deliberately given a false account, they were guilty of the "most wicked conduct". They would be taking away a man’s life through perjury, which in itself is a form of murder. Commenting on the disparity in the number of shots, the judge said that if Noonan and Ashton's evidence was "a concoction, what difficulty would there be in their adding that there were two shots"? The judge ruled out a verdict of manslaughter. The jury's two options were guilty or not guilty, with a conviction likely to mean the death penalty for Shaw.

The summing up lasted almost two hours and at 2:45pm the jury retired to consider their verdict. These days a murder trial lasts several weeks if not months, but Shaw's was done and dusted in less than two days. The jury returned to the court room at 3:40pm and delivered a unanimous verdict of "Not guilty" to the charge of murder. Shaw received the news without emotion and when formally discharged, left the courtroom in silence. Precisely what happened on that fateful night in August will never be known, although there is an interesting anomaly. Michael Noonan's death certificate states that the cause of his death was 'wilful murder' when the murder trial jury thought otherwise.

On Michael Noonan's memorial in St.Anne's churchyard there’s a request for people to pray for his soul. Perhaps prayers should be said instead for James Shaw's.

Legal and Illegal Beating of Boys in Old Sutton

It’s funny how times change. On August 9th 1869, five boys appeared in front of St.Helens magistrates charged with stealing from a house in Peasley Cross Lane. John Gaskill, Henry Leonard, Thomas Johnson, Edward Heeney and Peter Rigby were aged between 8 and 15 and had stripped the unoccupied house of bells and gas piping. The justices said that as long as the children were given a flogging by their parents in front of a policeman, they wouldn't take it any further. These days if parents are observed by the police physically punishing their kids, they are likely to find themselves in the dock!The advantage of a father administering a court ordered punishment himself was that his son would not receive a criminal conviction. However courts instructing parents to beat their law-breaking boys did not happen that often, although there were many cases of Sutton lads who were sentenced to receive strokes from a birch rod or twigs, often for relatively minor offences.

Curiously eleven years after the five lads were given paternal punishments for bell theft, 12-years-old George Ripley was given six strokes with a birch rod for stealing another bell. This was also from an unoccupied Peasley Cross house and George also nicked a small quantity of coal, along with his nine-years-old pal Thomas Eccleston. The younger lad escaped a formal whacking, although he was handed over to his father for 'correction', which probably amounted to the same thing!

I wonder if any of these Sutton lads, pictured in Robins Lane, Edgeworth Street and Watery Lane, ever get the birch?

I wonder if any of these Sutton lads, pictured here in Robins Lane (left), Edgeworth Street (middle) and Watery Lane (right), were ever birched?

Were these Sutton lads ever birched?

On July 26th 1886, John Makin aged 7 and Samuel Ellam aged 10 of Mill Row in Sutton were both charged with lifting the brakes of railway wagons with intent to upset and destroy them. As a result the train had run down an incline and a quick-witted pointsman had to turn them into sidings at Nuttall's bottle works. This stopped the wagons from going onto the main line, however they ended up hitting a warehouse and causing damage of about £16. The magistrates said it was a very serious case and but for the extreme youth of the defendants, they would have been dealt with more severely. They were still fined £1 each and given six strokes of the birch rod. Then they had their parents to answer to!

Then on June 4th 1898, Thomas Rattigan of 6 Watery Lane and Richard Lewis of 32 Marsland Street appeared in court charged with stealing a duck. The two 12-years-olds had captured the wildfowl on some waste land behind Watery Lane and then sold it to Mary Barton of the Red Rat in Ellamsbridge Road for 1s. 6d. Their business enterprise was rewarded with eight birch strokes each.

The birch was seen as a short, sharp, shock and magistrates in ordering such a punishment, considered that they were giving the boy another chance. Although six strokes was the standard number, eight and a dozen strokes were sometimes imposed and even more could be ordered at the Crown Court. On December 11th 1862 at South Lancashire Assizes, 13-years-old John Edward Allcock of Appleton Street, Peasley Cross, was ordered to be struck by a birch rod twenty times and sent to prison for nine months. His crime was allegedly setting fire to a haystack containing 18 tons of hay belonging to farmer Richard Baxter. Young Allcock had been spotted five yards from the stack but hadn't actually been seen igniting it. Despite his denials and another witness giving evidence that there was a second boy on the site at the time, John Allcock was found guilty by the jury.

Twelve-years-old John Parry was also given corporal punishment for committing a crime on Baxter’s farm in February 1856. The boy had only helped himself to some potatoes, although he was a recidivist offender. The police administered the punishments at their police station or at the court itself, but it was only boys who were struck during Victorian times. The practice of birching or whipping girls stopped in the 1820s. They were usually warned, fined or imprisoned as in this example:

Alice Jones - described simply as a child in one report - was jailed for three months on June 27th 1854. The girl picked the pocket of a woman named Ann Turner in Peasley Cross Lane, stealing 5 shillings.

L to R: a) Boys in Herbert Street; b) Girls had no fear of the birch (pictured in Herbert Street); c) Kids in Robins Lane

Girls had no fear of the birch - children in Herbert Street and Robins Lane

Kids in Herbert Street and Robins Lane

Jane West was a schoolteacher at Holy Trinity Schools in Peasley Cross and on September 4th 1882 she appeared in court charged with assaulting a 12-years-old pupil. John Parr couldn't answer a geography question, so his teacher struck him over the head with a cane causing a lump to rise. Miss West also caned him on his back and shoulders, which bruised him to such an extent that he could not lie down without pain. Her defence argued that the boy had received no more than necessary chastisement for unruly conduct and the blow to the head was an accident. The magistrates fined Jane West 2s. 6d.

Dennis Ratigan of 56 Watery Lane was sent to prison for two months on March 23rd 1900 for thrashing his 9-years-old son John with a carter's heavy whip. He'd beaten his son before but this time the boy had to be treated in hospital. Then on January 24th 1902, Cannington Shaw foreman Joseph Whitehouse was charged with assaulting boy labourer Gilbert Welsby. The 15-years-old claimed he'd been struck from behind, kicked and thrashed with the buckle end of a belt. Whitehouse's defence was that he held 'in loco parentis' responsibility for the lad, so had every right to chastise him for neglecting his work. This was clearly a difficult case for the magistrates and they chose to make the defendant simply pay the court costs. Just what life was like for young Gilbert when back at work under Whitehouse's 'care' after he'd prosecuted him, isn't recorded!

Corporal punishment administered in a controlled way by a police officer was considered acceptable by the social norms and values of the times. It was a deterrent sentence designed to stop boys from re-offending, as well as sending out a message to other lads. Physical chastisement by parents, or those with similar responsibilities, was also considered acceptable, indeed necessary when children misbehaved. However it was unacceptable for a teacher to strike a child on the head with a cane or for a parent to beat a boy so that hospital treatment was needed. There was a thin line that separated chastisement and assault. Although as was seen in the Joseph Whitehouse example, it often proved difficult for magistrates to decide if the line had been crossed.

Whether the birching of boys successfully deterred them from a life of crime and made them into honest citizens is an open question. However being incarcerated instead of being birched didn’t make Thomas Tierney 'go straight'. On October 11th 1869, when aged 10, he was sent to prison for a month by a hard-line magistrate. After serving his time, Tierney was ordered to spend a further five years in a reformatory, all for stealing nails from Kurtz’s chemical works. Then in 1882 at the same court session that fined schoolmistress Jane West half a crown, the now grown-up Tierney was charged with breaking into a St.Helens pub and robbing its till of £8. Certainly being put into the company of criminals and "bad lads" didn't direct Tierney onto the straight and narrow.

Judicial birching lost its popularity during the twentieth century and was finally outlawed on mainland Britain in 1948.

Seduction of a Sutton Builder's Daughter

In the article 'Breach of Promise and Seduction of a 17-Years-Old Sutton Girl', I described how Joseph Greenough was sued for not keeping his promise to marry Margaret Critchley. As the Sutton Glass Works fitter had got the daughter of the Mechanics Arms landlord pregnant, he was also sued for seduction. Greenough didn’t contest the paternity but in Fisher v. Jackson, the defendant certainly did. This was quite a different seduction case as the protagonists were well off and there was no question of a wedding. This was because defendant Robert Jackson was already a married man with three children.This case has a number of interesting aspects. It exemplifies once again how in Victorian times, juries and judges had great difficulty in reconciling one person’s word against another. Although as described in 'The Shooting of Michael Noonan' above, modern-day juries can still have this conflict, they are assisted by forensic and DNA evidence in reaching their verdicts. On December 8th 1888, when Fisher took on Jackson, there wasn’t even a test to determine the paternity of a child. Also of interest is the defendant’s admission that he had bribed two St.Helens newspapers not to print details of his case!

The plaintiff in this action for damages, which was held at the Liverpool Assizes, was John Fisher, a master builder from Robins Lane. He had nine children and he brought the action on behalf of his second daughter Elizabeth. Although the Manchester Courier described it as 'for the loss of his daughter Elizabeth's services owing to her having been seduced'. In court Fisher was described as advanced in years and suffering from ill health.

The defendant Robert Jackson was a timber merchant from Rainhill, whose sister ran a confectioner’s shop in St. Helens. In 1885 when Elizabeth was seventeen, she was apprenticed to the Church Street shop. Jackson regularly dined there and it was claimed by Elizabeth that their relationship began after he had complimented her on her cooking. He was soon allegedly making advances to the girl and on the evening of July 31st 1886, after she had remained at the shop later than usual, Jackson offered to take her home. In between Peasley Cross and St. Helens Junction it was alleged that 'seduction' took place.

Her father immediately began legal action against Jackson and a hearing was first held in St.Helens. An affiliation order was issued which required Jackson to make 5s. a week child support payments, although he denied paternity and lodged an appeal. In court at the Liverpool Assizes, where he was separately being sued by the Fishers for seduction, Jackson admitted having paid two St.Helens newspapers to suppress reports of the affiliation order. One, the St.Helens Chronicle, was given £3 not to print anything.

When Elizabeth gave evidence she effectively claimed that she’d been raped. She said that she had resisted the "improper intercourse", although admitted to Jackson’s counsel that she had not screamed. She denied when under cross-examination that any other man had ever "taken liberties with her". Miss Finney, an assistant at the Church Street confectioner’s, told the court that Jackson used to "kiss and tickle" Elizabeth in their shop but didn’t do it to the other girls. A young man named Fletcher also gave evidence that on one occasion he had seen the couple together on a train.

However the defendant vehemently denied an association with the girl and being the father of her child. Indeed on July 31st 1886, when the first "act of seduction" was said to have taken place, Robert Jackson claimed that he was staying in New Brighton. Several witnesses gave supporting testimony that he was living there with his family at the time. He also denied travelling with Elizabeth in a railway carriage or having "kissed or tickled" her.

The judge in his summing up seemed to be struggling with the claim that a respectable man like Jackson would behave as was alleged and that Elizabeth could have allowed it to happen. Justice Grantham told the jury that the plaintiff’s case was "almost incomprehensible". He said it was "practically unheard of” that a girl should have "allowed herself to be dishonoured" in the way she had described. He also gave little weight to the corroborating evidence of Miss Finney and Fletcher, saying that confirmation of Elizabeth Fisher’s claim was "extremely slight and slender" and the case rested "almost exclusively" upon her evidence. He was, however, impressed with Robert Jackson's "positive evidence", which mainly relied upon him proving he was in New Brighton when he was said to have been with Elizabeth in St.Helens. It didn't seem to occur to the judge that the girl might have got the exact date from 2½ years ago wrong!

Juries in those days didn't typically spend very long coming to a decision and the 2 hours and 40 minutes that the jury spent discussing Fisher v. Jackson was unusually long. In fact the judge had already gone home by the time the foreman brought in the news that they weren’t able to agree on a verdict. So a deputy discharged the jury in the judge’s absence and Elizabeth Fisher's public humiliation was over.

It was not a crime to kiss in St.Helens, but if it went any further....

The Brutal Murder of Walter Davies

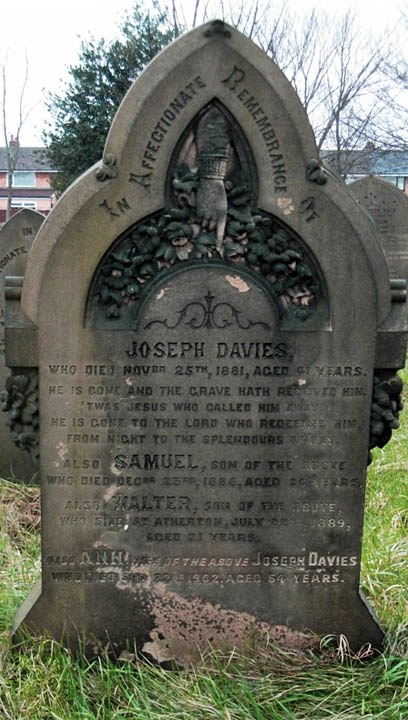

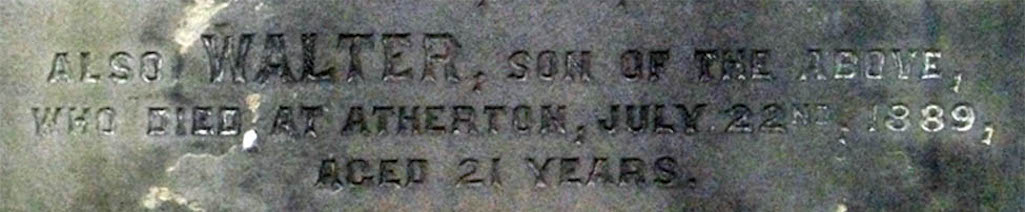

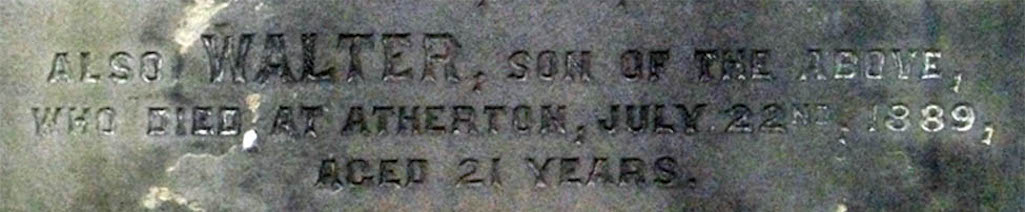

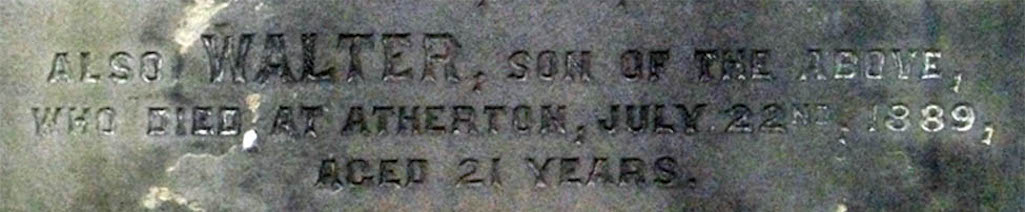

His devastated mother Ann was unable to control her grief and exclaimed: "Oh, my murdered Walter! Don’t tell me my Walter is murdered. What have they murdered him for?" She was so distraught at the loss of her young son that she had to be carried from his grave. Walter’s brutal murder in Atherton near Wigan had shocked the nation and his mother’s rhetorical question was a fair one. The answer was his life was taken for £60 worth of watches and chains, which the killer pawned for a fraction of their value.

Walter’s mother, Ann Harrison, was born in Sutton c. 1839. Upon marrying Joseph Davies, the couple moved to Widnes where they ran the Railway Hotel in Victoria Road. There they had four children, all boys, with Walter born in 1868. When Joseph died on November 25th 1881, aged just forty-one, he was buried in Sutton. Ann wished her family’s final resting places to be where she’d been born and bred. When her oldest son Samuel died on December 23rd 1888 aged 26, he was interred in the same grave as his Dad. Ann’s third-born son Walter made regular visits to the Sutton churchyard to pay his respects to his father Joseph and brother Samuel. He could hardly have imagined that within months he would be sharing the same grave with them.

Despite the setback of Samuel’s death at Christmas 1888, the family’s fortunes were generally improving. Mother Ann had married a man named Dodd and Walter was himself engaged to be married. The 21-years-old also had the prospect of a good job having been offered a position working for pawnbroker John Lowe at Atherton. Lowe had his main shop in Market Street but also owned a lock-up some 300 yards away where jewellery, watches and articles of clothing were sold.

Walter began his employment in May 1889 and seems to have made a positive impression with his employer. The young man had sole charge of the lock-up and his daily routine began just after 7am when he collected the shop keys and a case containing watches, chains and jewellery from John Lowe. Then each evening after the day’s trading had ended, Walter returned the keys and the unsold valuables to his boss who put them in his safe. On Monday morning July 22nd, Walter picked up the keys and case at the usual time. However a gale had blown a few days earlier and much water had got into the cellar of Walter’s shop. There was now a strong smell, so Lowe instructed Walter to wash out the cellar which seems to have been his undoing. At 9.10am, Walter was found dying in the cellar of 29 Market Street having received a severe wound to his throat plus head injuries. A post-mortem later revealed that his skull had been cracked all over.

It was surmised that the killer had found the shop empty and began helping himself to merchandise. After being disturbed by Walter, he’d attacked him and then left the young man dying in the cellar. Several watches were found to be missing, as well as silk handkerchiefs plus other items of clothing. A number of watches were pawned at various pawnshops in Manchester and Liverpool but the police for some time seemed baffled as to who was responsible. They did make several arrests and a man called John Lorn was charged with the murder, but was eventually able to prove that he was in Blackburn on the fateful day. However it was Lorn's arrest and incarceration on remand at Strangeways Gaol that led to the finger being pointed at William Chadwick.

Chadwick was a self-confessed thief who robbed suitcases on trains by simply telling trusting guards that they were his property. He was finally caught and remanded to Strangeways where he was said to have remarked that John Lorn was an "innocent man". This seems to have been a casual comment after reading a newspaper, but it was sufficient to increase police interest in him. As Chadwick was known to be very well acquainted with pawnshops and had a record of violence, the detectives were already wondering if he might be their man. Pawnbrokers then identified Chadwick as the man who had pawned stolen watches and there was also handwriting evidence against him.

William Chadwick vehemently denied that he was the killer but he was found guilty of the crime and on April 15th 1890 at precisely 8am, was hung in Kirkdale Gaol. His last words were "Good-bye; God bless you all." A large crowd that had gathered outside were able to hear the distinctive sound of the trap doors falling inside the prison and watch a black flag being hoisted. The latter signified that the deed had been done. The evidence against Chadwick was largely circumstantial and he left touching, lengthy letters to his brother Thomas and wife Polly in which he said his goodbyes and pleaded his innocence. The executed man left instructions for the letters to be published in the newspapers and he wrote another letter to be dispatched to the Home Secretary after his death.

One would not know what had happened to Walter Davies from the simple inscription on his memorial in St.Nick's

One would not know what had happened to Walter Davies from his gravestone

The Walter Davies memorial in St.Nick's

Red Tape in Old Sutton

I have always assumed that the wide-ranging regulation of business is a relatively modern phenomenon. After all there were no Trading Standards officers during the Victorian era and quite limited health and safety rules. It wasn’t until the 1960s that a raft of consumer legislation began to be passed and the 1970s that the Health and Safety Commission was established. However in researching old Sutton I’ve learned that what many business owners considered burdensome red tape was quite prevalent. This led to many business owners - usually small or sole traders - finding themselves up before the magistrates charged with relatively trivial offences. For example on April 5th 1889, Sutton coalman Thomas Barrow was fined 12s 6d, including costs, for selling 1½d of coal slack to women in tubs. He was in breach of regulations that stated that it could only be sold by weight. Then on July 26th of that year, taxi-driver Henry Bickerstaffe of Sutton Road was fined 10 shillings inc. costs for plying for hire a licensed horse-driven hackney carriage that didn't have his official number and the number of passengers painted on it.Eighteen months earlier on December 9th 1887, John Marsh of St.Helens Junction had appeared in court charged with hawking vegetables without a market certificate. A bewildered Marsh pleaded to the magistrates that he didn't know that he had to have a certificate (which cost 9d per day) for simply taking orders door to door. He was treated leniently and given a nominal fine of 1s plus costs. Although fines were rarely high, coupled with costs they could be the best part of a week’s wage. Plus there was the time spent and business lost in attending court. It didn’t do their reputations any favours either.

Much attention was paid to food regulation, with concerns over food quality and how it was sold increasing during the 19th century. This was largely through complaints by factory owners of poor performance by their workers, who were often fed on low quality, adulterated food. As a consequence provision store prosecutions were quite common, often for minor breaches of the rules. Alf Prescott ran a grocer's shop in Pecker's Hill Road and on June 22nd 1891 he was fined 10 shillings for simply selling margarine that wasn't branded.

Grocers' weights were regularly checked and the owners would find themselves in court if they weren’t bang on. On February 22nd 1869, two Sutton dealers, Enoch Newton and Hamlet Norris, were both fined £1 plus costs for having 'unjust' weights. Even farmers had their scales checked. On June 28th 1880, Thomas Johnson and John Newton, both farmers at Bold, were fined £2 and £1 respectively for having light scales. Newton’s were only slightly out, so probably felt hard done by. Magistrates could end up being prosecuted for breaking the rules. John Willis J.P. of 2 Reginald Road was fined 20 shillings on January 25th 1918 for selling milk 10% deficient in fat.

There were a number of different types, but the so-called ‘Connolly's’ tickets, which cost 1 shilling and were linked to horse racing, were the most common. It was said that as many as 15,000 tickets were in circulation in Lancashire at times, earning the organisers up to £400 per week. As well as buying lottery tickets, people purchased lists costing halfpenny a few days later to see whether they were a winner. The unlucky ones sometimes received a consolation prize of a pouch of tobacco.

Typical prizes ranged from 5 shillings to £100 but they often landed the sellers in court. On November 24th 1884, Sutton hairdresser John Houghton was fined the large sum of £10 plus court costs for selling Connolly’s tickets. Many shopkeepers said they were asked by their customers to sell the tickets and they strongly objected to the police purchasing them disguised as working men.

Some breaches of the Lottery Act were quite trivial but still landed Sutton shopkeepers in court. On October 28th 1892, Harriet Lacey of Ditch Hillock, Ann Kelly of 5 Fisher Street, Eliza Ann French of 12 Fisher Street and Mary Murray of 22 Appleton Street in Sutton appeared before the bench. They each owned a shop and had been caught in Sergeant Brooks’s sweets sting operation.

Their crime had been to sell packets of sweets that were a form of ‘lucky dip’, in which some contained coins. Sergeant Brooks testified that he had visited all the defendants’ premises and purchased packets of sweets, in some of which were halfpenny coins. On the bench was Sutton’s own Arthur Sinclair of Waterdale, who was minded to be lenient to the female shopkeepers. They must have been horrified to find themselves in court and fines were imposed on each of 2s 6d plus costs.

Towards the end of the 19th century with the increasing numbers of pubs and beerhouses and a rise in drunkenness, the police were paying special attention to licensed premises. Sometimes prosecutions involved pedantic infractions of the rules and a common court case was of keeping a licensed house open for the sale of beer during prohibited hours. However just how you defined ‘open’ and ‘sale’ of beer was not quite as straightforward as might be thought.

On November 4th 1889, the landlord of the Golden Cross, Samuel Cox, was summoned for keeping his house open for the sale of beer at 11am on Sunday October 27th. Evidence was given by the aforementioned Sergeant Brooks and PC Small that they had observed two men named Howard and Highfield walk along the railway into Sutton's 'Pudding Bag' district. They then watched the pair climb over the pub’s back wall and enter the kitchen.

The police followed and saw the landlord serving them beer. Highfield put down a shilling for payment but Sgt. Brooks picked the coin up without the landlord touching it. Cox said the men had told him they'd travelled from Widnes, so could legally be served under the traveller rules for inns. The magistrates, Colonel Gamble and Alderman Cook, said they were satisfied that Cox had intended to sell the men liquor. However, as the pair had had to scale an eight feet high wall to get their beer, the Golden Cross could hardly be described as being open.

The second charge of selling beer was similarly dismissed. Although the traveller excuse was disallowed as the men only lived in Bold Road, just half-a-mile away, the landlord did not actually receive any money. So technically a sale had not been made and for once the rules that many traders felt were pedantic and technically applied, worked in Samuel Cox's favour.

Connollys Ticket - Note lottery number

A Case of Poetic Justice in Sutton Manor

Just why some of the new Sutton Manor streets were given the name of poets doesn't seem to have been recorded. Alfred Tennyson, the Victorian Poet Laureate, has no known association with St.Helens but his name was given to the road opposite the new pit. Of course it was Tennyson who wrote 'Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all' and 'Theirs not to reason why, theirs but to do and die'. Just whether unrequited lover George Cottle had these words in mind when he attempted to murder his landlady and then kill himself, isn't known. However his violent acts at 30 Tennyson Street led to the Sutton Manor miner serving ten years in prison where he could read poetry to his heart's content.

Cottle resided with fellow miner William Fleming and his wife Ellen and their two children, along with another lodger. It used to be the norm for single men to lodge with families. Letting a room did mean extra income, although it often led to crowded houses and less privacy. Occasionally there was intimacy between landlady and lodger and in some cases couples ran off together. This was considered quite scandalous and in one case of elopement in Parr in August 1882, there was a near-riot as the local community displayed their disapproval.

Cottle was 28 and had lodged with the Flemings from August 1913 when they were living at Warrington and he'd become infatuated with Ellen. In September, for some reason, William deserted his wife for which he was sent to prison for a month. During his absence the lodger began a brief relationship with his landlady or as Ellen later put it in court, they were on "familiar" terms with each other.

On Sunday 22nd March the two men were due to begin the same early shift at Sutton Manor Colliery. Ellen cooked breakfast for them both but Cottle suddenly announced that he wasn’t going to work that day. He claimed he was instead travelling to Warrington to pay off his insurance, which seems to have been a ploy to get Ellen on her own. After her husband had departed for work, Ellen put a kettle of water on the fire and Cottle asked her what she was planning to do. Ellen told him to go away but moments later he seized her and hacked her throat twice with a razor. "Me and you will have to die together", exclaimed the miner before cutting his own throat.

The other lodger sleeping in the house was woken and had the unedifying spectacle of seeing Cottle and Ellen standing over him with blood pouring from their throats. The house was said to have been drenched with blood with Ellen’s wounds the worst. If the cuts had been 1/16th inch deeper, she would have died in the house. As it was her wind pipe was half cut through and her blood vessels laid bare.

An aerial view of Tennyson Street photographed from Sutton Manor Colliery during the 1960s

An aerial view of Tennyson Street from Sutton Manor Colliery during the 1960s

An aerial view of Tennyson Street

At the Liverpool Assizes on April 23rd 1914, Cottle was charged with wounding with intent to murder as well as attempted suicide. His defence counsel claimed extenuating circumstances through ill-health, explaining that his client had recently suffered with his head and eyes and didn’t know what he was doing. The jury found Cottle guilty and Justice Bray in awarding a sentence of 10 years said he could find no mitigating circumstances.

Like most articles on this website, this story is sourced from a number of newspaper articles. Their coverage of crime and tragic events invariably stops with the sentencing or inquest verdicts, leaving open a number of questions. In this case I wonder what ever happened to Ellen? Was she able to put all this behind her? Did her husband William stay with her? Did they remain at Sutton Manor or did the notoriety mean that they had to move? What was the effect on their children? Questions that we’ll, unfortunately, probably never know the answers.

'The Very Strange Case' of Alderman Boscow

Sutton has been the home of four notable Mayors of St.Helens. Henry Baker Bates, Arthur Sinclair and Joe Murphy were well-loved figures but Thomas Boscow was very controversial. Older Suttoners might just recall his tobacconist's and newsagent's shop at 6 Junction Lane but his attempt at bringing down St.Helens's top cop in 1927 and a court case after a robbery in 1935, led to much criticism.

It wasn't long after his election that Councillor Boscow had his first run in with the law. On June 9th 1922 he was fined £9 in St.Helens Police Court after being charged with intimidation. On the following day while sitting down for his lunch, Boscow was arrested on suspicion of perjury and kept in police custody for six hours. They were acting on a complaint from a barrister but the councillor was later acquitted at Liverpool Assizes.

In October 1922, Cllr. Boscow became unpopular with many St.Helens Corporation officials. He moved a resolution that called on them to allow their salaries to be cut or face the sack. The Mayor, Richard Ellison, complained that Boscow was making the Council look ludicrous. In 1923 he joined the Corporation's Watch Committee and was its made Chairman three years later. Although Watch Committees are remembered mostly today for the banning of controversial films, their primary duty was to regulate their local police force. In 1964 they were replaced by Police Authorities who have themselves recently been replaced by Police and Crime Commissioners.

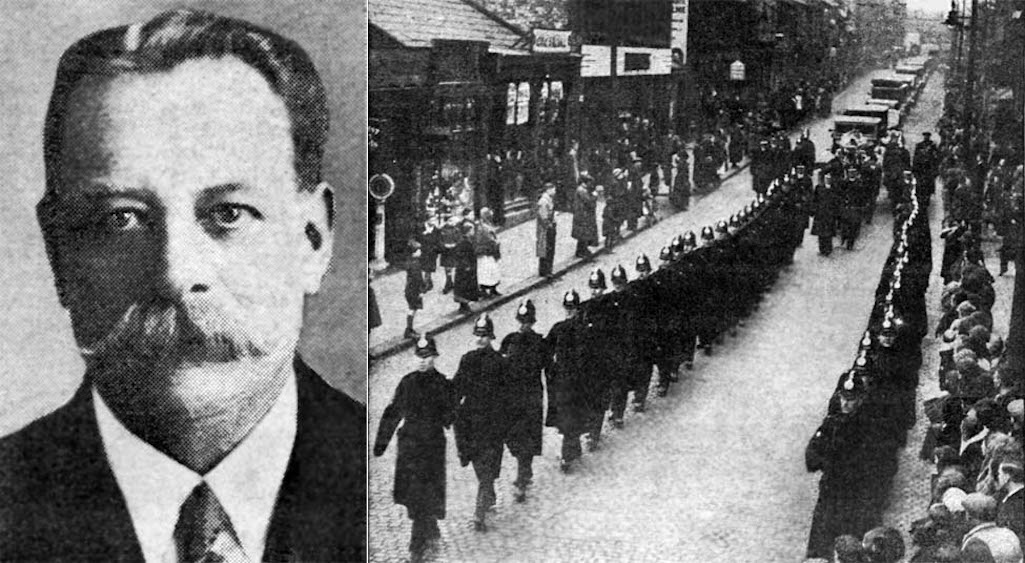

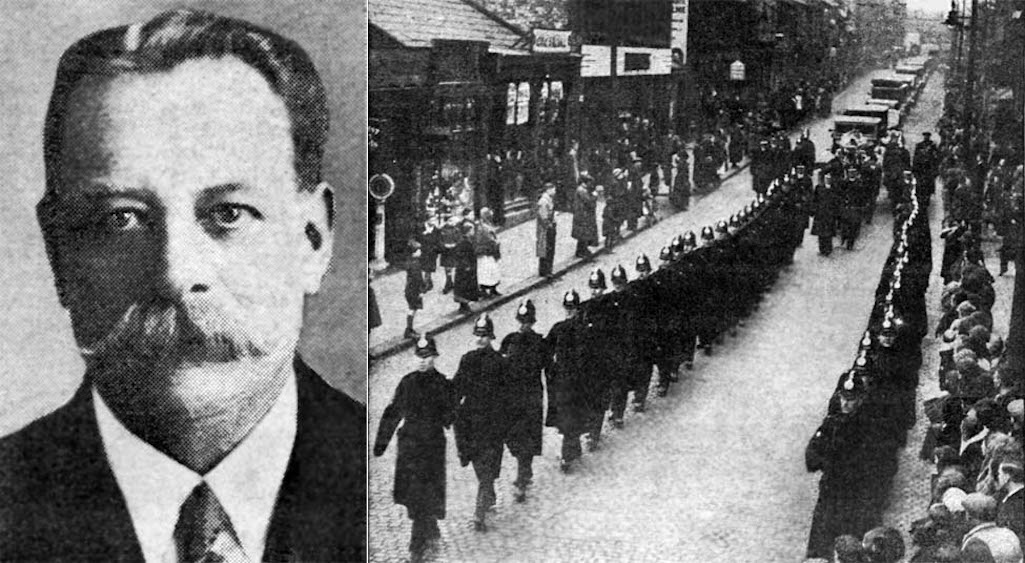

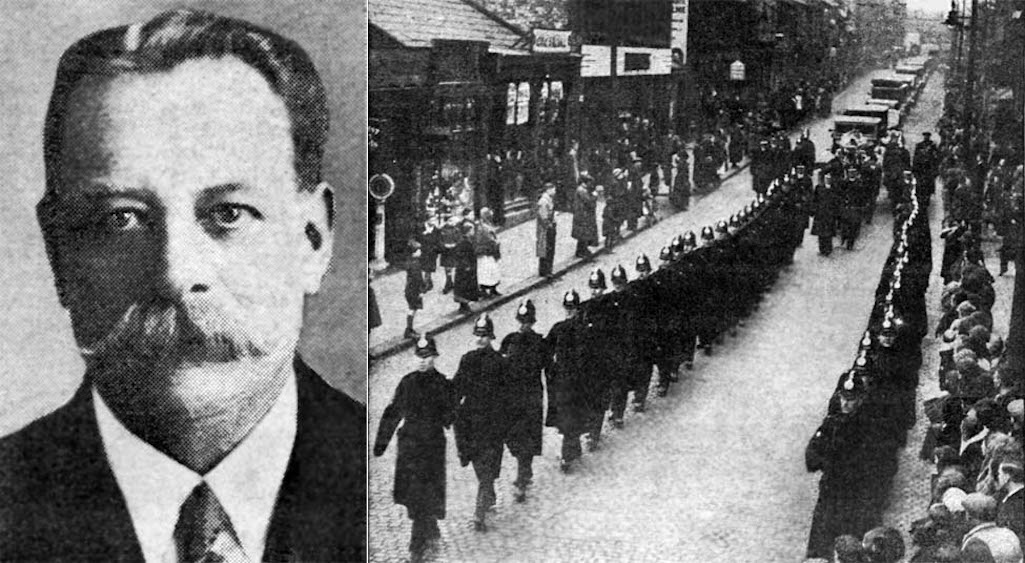

Left: Chief Constable Arthur Robert Ellerington; Right: HIs funeral procession on March 2nd 1939

Chief Constable Arthur Ellerington and hIs funeral procession in 1939

Chief Constable Arthur Robert Ellerington and his funeral procession

The young PC Ellerington didn't pound his Bridlington beat for very long. Within two years he had transferred to the West Riding force, becoming Detective Chief Inspector. In 1902 Ellerington became Britain’s youngest chief constable when appointed to run Margate police. Then in December 1904 he got the top police job in St.Helens, beating 88 other candidates.

Chief Constable Ellerington's simmering dispute with Boscow - and the other Labour members of the Watch Committee - worsened during the 1926 strike and miners’ lock out. The now Alderman Boscow was charged with intimidation and was subsequently bound over in court. His Watch Committee was also accused of interfering in the Chief Constable's deployment of his officers at the collieries when Liverpool bobbies supplemented the local force. The St.Helens Reporter was severe in its criticism, claiming it was proud to expose 'the plotting of the Labour party' in the town.

In articles published in October and November 1926, the Reporter claimed the Labour-run Watch Committee had plotted to remove 50 Liverpool police officers from St.Helens. Accusations were also made that the police and coal owners had been warned by Labour members that 'when their time came', it would be a case of 'God help them'. This reinforced a concern by many that as the socialists won more power both locally and nationally, there would be a payback for perceived past wrongs.

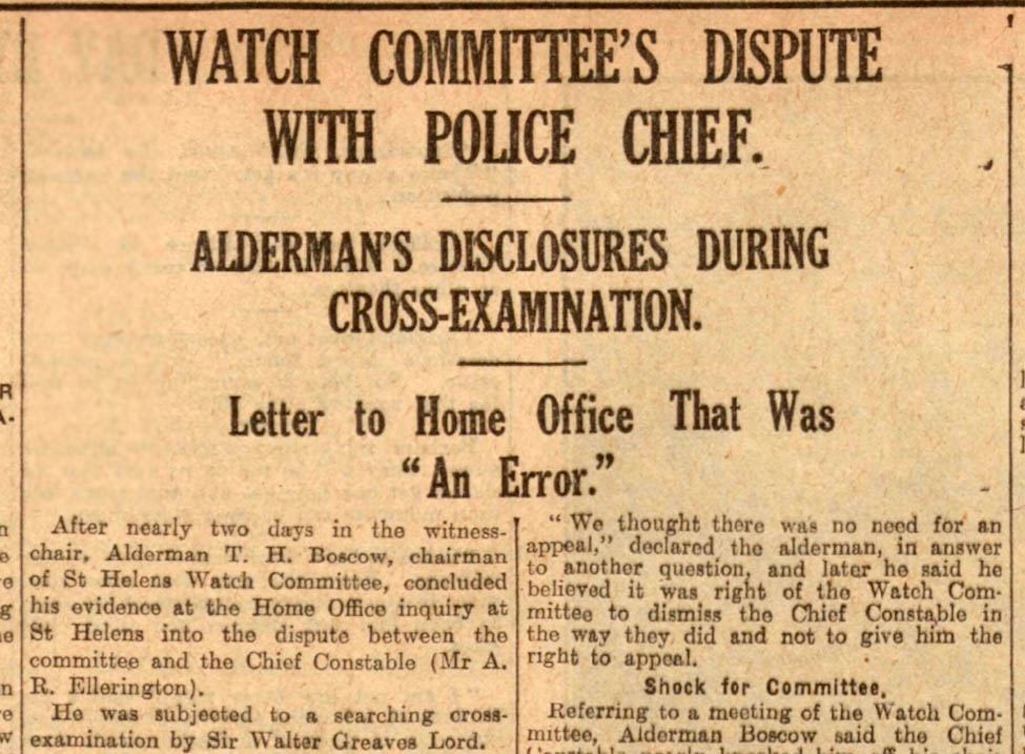

It all came to a head after Ellerington had foolishly turned up at the McCormick’s house looking for a PC with a grievance. Ellen McCormick said he had insulted her and at a Watch Committee meeting on September 14th, the socialist members accused the Chief Constable of bullying, corrupt practices and misconduct. A resolution was then passed by the committee ordering the police boss to retire. Boscow despatched the Town Clerk to the Home Office to try and persuade them not to permit an appeal. This was unsuccessful and an official inquiry took place on November 4th. Sir Walter Greaves-Lord represented Ellerington, a name that will have greater significance later in this article. However Boscow's watch committee boycotted the inquiry and on November 23rd the Home Secretary overturned the committee's decision.

However the Watch Committee protested and parliament ordered another board of inquiry in which witnesses would be on oath. This was held at St.Helens Town Hall and began in mid-March 1928. The seventeen-day-inquiry was conducted by Thomas Hollis Walker the Recorder of Derby and Charles de Courcy Parry, Government Inspector of Constabulary. Sir Walter Greaves-Lord again represented Arthur Ellerington. Boscow told the inquiry that the Chief Constable had been uncivil to the Watch Committee and "time and again" he’d had to appeal to him not to bully his members.

The alderman claimed that Ellerington also bullied his men and was a man of violent temper who frequently lost control. He also alleged dissatisfaction within the force that would likely hamper future recruitment. Boscow spent eight and a half hours giving evidence, much of it being intensively grilled by Greaves-Lord, Ellerington’s counsel. At one point in his interrogation, he got Boscow to admit that "questions of justice did not arise at all" to which the KC replied "Well, that’s candid".

Evening Telegraph 21st March 1928 - The dispute between the Chief Constable and Watch Committee was widely reported

The dispute between Ellerington and the Watch Committee was widely reported

Evening Telegraph 21st March 1928

The Chief Constable of Chester, Thomas Griffiths, who had joined the St.Helens force as a constable in 1903, said his former boss was strict but fair. He described drinking, gambling and fighting in the police barracks when he first joined but Ellerington had greatly improved discipline and training. Griffiths continued that his former boss had had "no use for slackers" but was most helpful to PCs who wanted to improve themselves. Indeed on February 2nd 1914, Ellerington had been presented with an 'illuminated address' by Chief Inspector Dunn on behalf of the force as a mark of the high esteem that he was held. The men praised their boss for providing many benefits, including improving their pay, provision of a recreation club plus "innumerable acts of kindness".

The inquiry by Hollis and Walker cost £10,000 and their report published in May, completely exonerated Arthur Ellerington. They put the blame for the dispute firmly on Aldermans Boscow and Waring, who they believed had baited and worked against the Chief Constable. The friction, they believed, had begun in 1923 when Boscow, with his "deep resentment" of his arrest during the previous year, had joined the Watch Committee. Ellerington was reinstated after nine months suspension and in June 1934 was awarded £2000 damages for slander as a result of an accusation made against him by Ellen McCormick.

The dispute and public enquiry attracted much newspaper coverage throughout the country and didn’t reflect well on St.Helens. One might have thought that Thomas Boscow would have felt his position to be untenable after such a critical official report. However he not only continued as chairman of the Watch Committee for many years but within a few months of the report's publication, he was elected Mayor of St.Helens. That isn’t the end of the story as in October 1935, Boscow gave evidence in a trial at Liverpool Assizes. Despite being the victim, he was heavily criticised by the judge who declared it "a very strange case". Remarkably, 'His Honour' was Boscow’s old adversary from the Ellerington inquiry, Sir Walter Greaves-Lord, who had given him such a tough cross-examination.

Alderman Boscow had met William Mitchell late one night at Lime Street station when on his way to London. Mitchell asked his help in getting a job and on his return from London, Boscow sent him a form to complete. Claiming he couldn’t fill in the form, Mitchell turned up at his Junction Lane house and stayed the night. He returned at a later date with Crosby in tow and the pair shared a bedroom over the shop. Locked inside a wardrobe was a deed box containing savings certificates, securities, a leather cigar case and a gold medal.

Boscow discovered that the box was missing and the Liverpool police found it at Crosby's sister's home. Mitchell made a number of unspecified allegations about Boscow but later retracted them. The pair were found guilty but it seemed as if the Alderman, who was still chairman of the St.Helens Watch Committee, was in the dock. Justice Greaves Lord was scathing about the bachelor Boscow's behaviour in his summing up to the jury:

Thomas Hill Boscow sold his tobacconist’s shop at 6 Junction Lane during the late 1930s and returned to live in Warrington. Just a few years later, in December 1941, a terrible tragedy struck at his former business when four members of the Baron family lost their lives through a gas leak. Boscow himself died in Warrington General Hospital on March 30th 1951 at the age of seventy-four. Boscow Crescent, off Gerards Lane, bears the controversial Sutton alderman’s name.

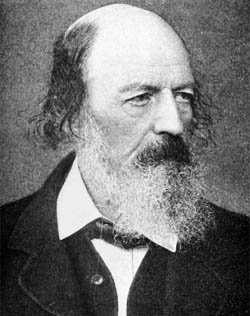

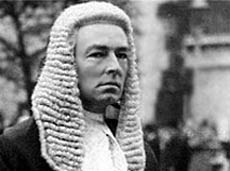

Sutton Judge Sir Bernard Caulfield (1914 – 1994)

It’s often the case that well-known people are remembered for just one thing after death. Comic Harry Worth is remembered for the optical illusion in the opening titles of his television series, rather than his long career in TV, radio and the stage. So is the case with Sir Bernard Caulfield. The Sutton judge is recalled by many purely for referring to the "elegance" and "fragrance" of Mary Archer in her husband Jeffrey's libel case of 1987. However he had a distinguished career as a high court judge for over 20 years and was renowned for his common touch and common sense approach to cases. He once said "People think of us Judges as so stuffy but we are not".Bernard Caulfield could never have been described as stuffy. He was born on April 24th 1914 in Peckers Hill Road and baptised on May 3rd at St. Anne’s RC Church. The son of John and Catherine Caulfield, his mother later kept a shop at 174 Mill Lane, near Grimshaw Street by the Mill House pub. Some are said to have dubbed that part of Mill Lane “Cockroach Row” and the shop was run for many years into the 1960s by Bernard’s sister. Young Bernard’s primary school education was at St. Anne’s RC school and his secondary schooling was at St. Francis Xavier’s College in Woolton. After his death in 1994, one unnamed Suttoner was quoted as saying "I well remember Sir Bernard in his student days. He was always whistling as he headed for the Junction station to catch the Liverpool train".

After graduating from the University of Liverpool, Bernard qualified as a solicitor. His 30-year legal career was interrupted by the second world war and he joined the Royal Army Ordnance Corps at its outbreak. Caulfield was then seconded to the intelligence corps in Cairo and demobilised in 1947 with the rank of major. Bernard went to the Bar that same year and was made a Queen’s Counsel in 1961.

Three images of Sir Bernard Caulfield (1914 – 1994) from Sutton who was a high court judge for 20 years

Sir Bernard Caulfield (1914 – 1994) from Sutton, a high court judge for 20 years

Sir Bernard Caulfield (1914 – 1994)

His two decades on the Bench were spent mainly as a circuit judge and with his roots in St.Helens, Justice Caulfield particularly enjoyed being on the Northern Circuit. He was renowned for his common sense approach to cases and was a stalwart supporter of the press. He once declared that "the Press must not be muzzled" and he called for Section 2 of the Official Secrets Act to be "pensioned off". At the Jeffrey Archer trial in 1987 he arranged for extra seating and tables for reporters, so none would miss out.

It was as a result of his references to Archer’s wife in his summing up of that case, that affected Sir Bernard Caulfield’s reputation. The author and politician had sued the Daily Star for libel after they had alleged that he’d paid for sex with a prostitute. The jury awarded Archer £500,000 and the judge added costs of £700,000. Some circles of British society, especially the tabloid media, felt Caulfield’s comments about the "fragrance" and "elegance" of Mary Archer were designed to sway the jury. Although it has to be said that the Daily Star chose not to pursue an appeal on that ground.

Justice Caulfield’s contribution to the proceedings had been far greater than his much-reported comments. The Glasgow Herald in its article 'Last of the Characters on the Bench' (25/7/1987), reported how the court had at times "rocked with laughter at his sallies". During his summing up the judge had also referred to the six yard box at Anfield, Cardiff Arms Park, the racetrack and the television series Pot Black to illustrate and clarify his points to the jury.

Sir Bernard Caulfield retired two years after the celebrated court case and died on October 17th 1994 at the age of 80. Despite living in Middlesex, he left instructions to be buried in Sutton. Bernard had retained his links with St.Helens and his brother Tom was the council’s Building Manager. Plus when Sutton Historic Society was founded by Eric Coffey in 1987, he had invited Sir Bernard to become its President. He readily agreed and served until his death.

Bernard Caulfield was buried in a simple family plot at St.Anne’s Church in Sutton in a service celebrated by Fr. James. Seven years later the now Lord Archer was imprisoned for four years for perjury at the libel trial that Justice Caulfield had presided over. His "fragrance" and "elegance" remarks were revived by the media and the judge’s reputation was further dented in the public mind.

Caulfield’s obituary in The Times commented on the "streak of mischief" in his judicial work and his use of "florid language" and "not always apt commentaries about human situations". However they also lauded the Sutton lad’s attributes, as having been a good judge with an "unquenchable thirst for individual justice, sound legal and independent judgment, an equable temperament and, nearly always, a sure touch in assessing human conduct and evaluating social attitudes." Sir Bernard Caulfield was extremely well thought of in legal circles, as well as in Sutton and St.Helens, and should be remembered for a distinguished legal career that lasted three decades.

Caulfield grave in St.Anne’s Cemetery